Each teacher and scientist partner who includes undergraduates in their partnership with teachers creates a case study at the conclusion of their groundwater project. This provides inspiration for others in terms of curricular activities, strategies for building school-community connections in the stewardship of groundwater, and replicable project design. Teachers can use the template below to construct their case studies!

Featured Case Studies 2024

Got Arsenic? Sip Safe with an Easy Solution: A Case Study of Bow High School, New Hampshire

Teacher Lucy Koup from Bow High School in Bow, New Hampshire, has a unique approach to engaging her students, as well as their parents, in the NIH SEPA “Communicating Data” drinking water project. Lucy leveraged parent-teacher conferences as an opportunity to distribute water test kits to parents and engage in face-to-face conversations about their student’s participation in the project, which involves collecting drinking water samples for analysis of arsenic and other toxic metals. By directly interacting with parents, Lucy encouraged them to be not only involved in collecting water samples from their homes but also aware of the potential health impacts of their own drinking water quality.

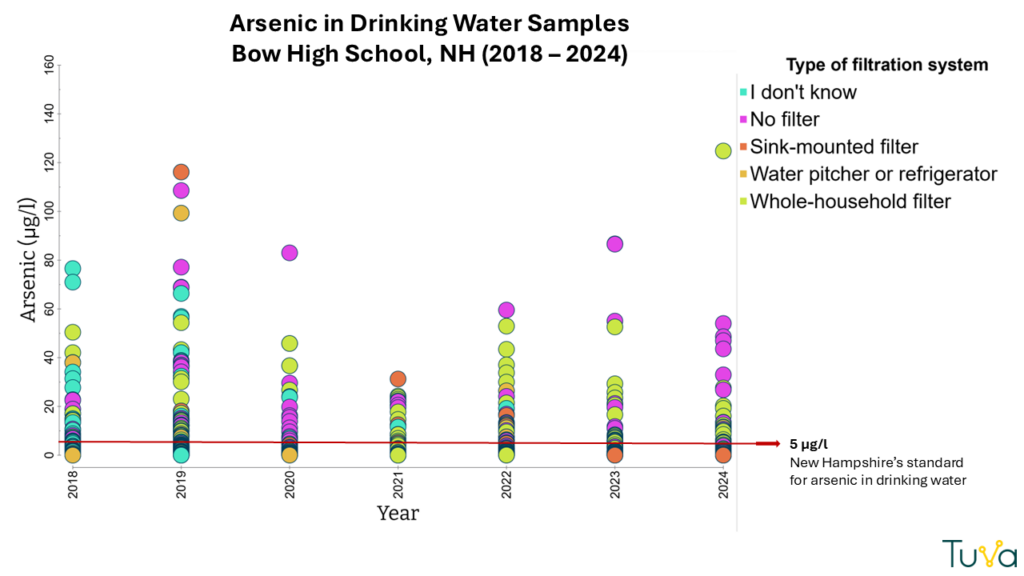

Arsenic levels in Bow’s water samples have been consistently concerning since high school students began collecting water samples in 2018. In 2019, students saw the highest number of samples with elevated arsenic levels, but the most elevated arsenic concentration recorded in the seven years of the project, at 124.8 μg/l, was in 2024 (Figure 1). The New Hampshire Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL) is just 5 μg/l. Interestingly, this record-high sample came from a residence with a whole-house filtration system. This suggests that the filtration system either wasn’t designed to remove arsenic, was malfunctioning, or suffered from lack of maintenance, rendering it ineffective.

Figure 1. Arsenic concentrations in selected drinking water samples collected by students from Bow High in New Hampshire between 2018 and 2024. Samples are categorized by filtration system type. The highest arsenic concentration, recorded in 2024, was found in a sample taken from a residence with a whole-household filtration system, marking the peak concentration over the seven-year study period.

After obtaining this year’s results, Lucy is determined to act. She is offering her students’ families ZeroWater® filters, known for their effectiveness in removing arsenic from drinking water (Barnaby et al., 2017). To ensure privacy, families will have the option to contact Lucy directly. Furthermore, Lucy is exploring the possibility of having her students build their own low-cost, Do-It-Yourself water filters in collaboration with the New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services as part of a hands-on learning experience.

Lucy is not the only teacher at Bow High School involved in the drinking water project. Two other chemistry teachers have their students contributing drinking water samples to the sampling effort. With three teachers working together, there is an excellent opportunity to build a collaborative community where best practices and resources can be shared. Additionally, Lucy maintains a connection with the Drinking Water Protection Committee, to which Bow High School students have given presentations in the past, further expanding the reach of the project and fostering potential community action.

Through her proactive approach, Lucy is making a lasting impact on both her students’ education and the well-being of the broader community.

References

Barnaby, R., Liefeld, A., Jackson, B. P., Hampton, T. H., & Stanton, B. A. (2017). Effectiveness of table top water pitcher filters to remove arsenic from drinking water. Environmental Research, 158, 610-615.

Kids Can Make a Difference: A Case Study of Westbrook High School, Maine

Ragan Hedstrom, a teacher at Westbrook High School in Maine, has exemplified teaching the concept of “Data to Action” to her students who are involved in the NIH SEPA project “Communicating Data,” thereby empowering them to translate information into meaningful, real-world advocacy.

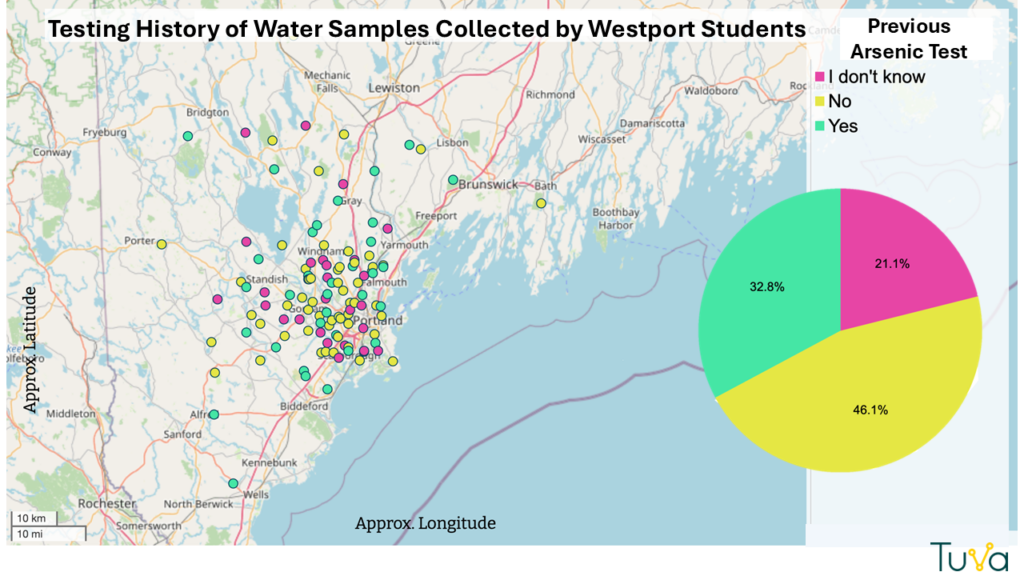

Based on data (2016-2022) from NIH SEPA schools in Maine, with 214 samples exceeding the EPA’s Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL) for arsenic of 10 μg/l (Figure 1), students at Westbrook High School decided to take action by participating in legislative advocacy, as described below.

In 2021, one of her students provided testimony during a public hearing, advocating for the passage of LD1570, a bill aimed at improving well water safety in Maine. The bill proposed measures to provide free well water testing for low-income residents, ensure that landlords tested well water for arsenic, and reduce the acceptable arsenic levels in community drinking water from 10 parts per billion (ppb) to 5 ppb (which New Hampshire and New Jersey have already done).

Drawing from the data her class had gathered from their drinking water project, the student demonstrated the bill’s potential positive impact on the broader Maine public, thus making a strong case for the legislative change. Unfortunately, this bill did not pass.

Figure 1. Nearly half (46.1%) of water samples collected by Westbrook students came from homes without a prior arsenic test, and 21.1% were from residents unsure about whether their water had been tested. This highlighted a significant need for arsenic testing in Maine, underscoring the importance of passing LD1570.

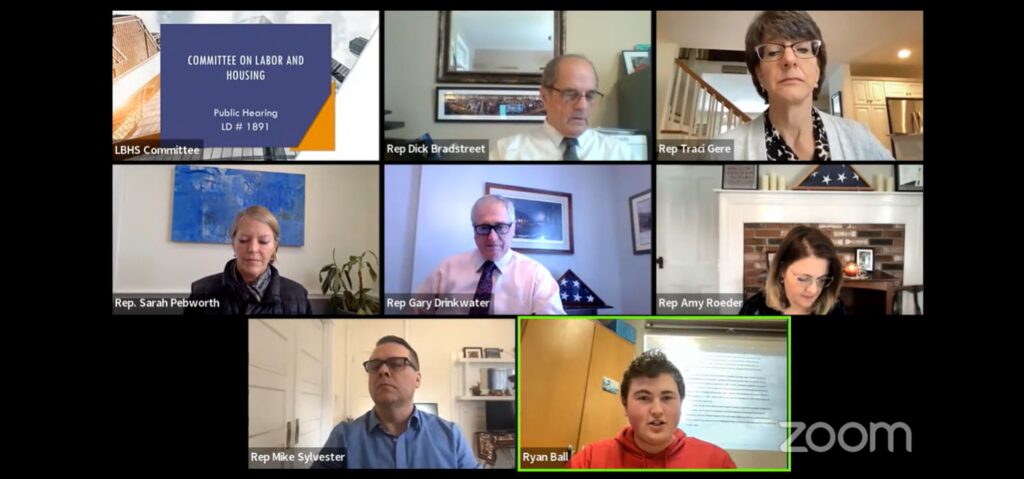

The following year, Ragan’s students engaged in another advocacy effort, this time supporting LD1891, a bill that would allocate grants for well water remediation in cases of contamination. One of Ragan’s students (pictured below on the bottom right) wrote a thoughtful and compelling testimony, asserting that access to clean drinking water is a fundamental human right. The student used relevant data to back up his argument, showing a clear understanding of how to construct a data-supported narrative.

Figure 2. Student Testimony at Public Hearing.

“Every citizen in this state should be given access to clean drinking water regardless of their income, and through the passage of this bill, Mainers will decrease their odds of developing adverse medical impacts from well water whilst our state as a whole becomes a more equitable and just one, as we attempt to solve a problem that boils down to a fundamental human right.” – Ryan Ball, student at Westbrook High School

Through these experiences, Ragan Hedstrom has taught her students a critical lesson that is underemphasized in education—how to effectively communicate data to advocate for change. Her approach highlights the power of education to connect students with critical social and public health issues and gives them the tools to make a tangible impact in their communities. In doing so, Ragan is teaching the next generation to become informed and engaged citizens capable of using data to drive positive change.

What’s up with Manganese? A Case Study of Swan’s Island School, Maine

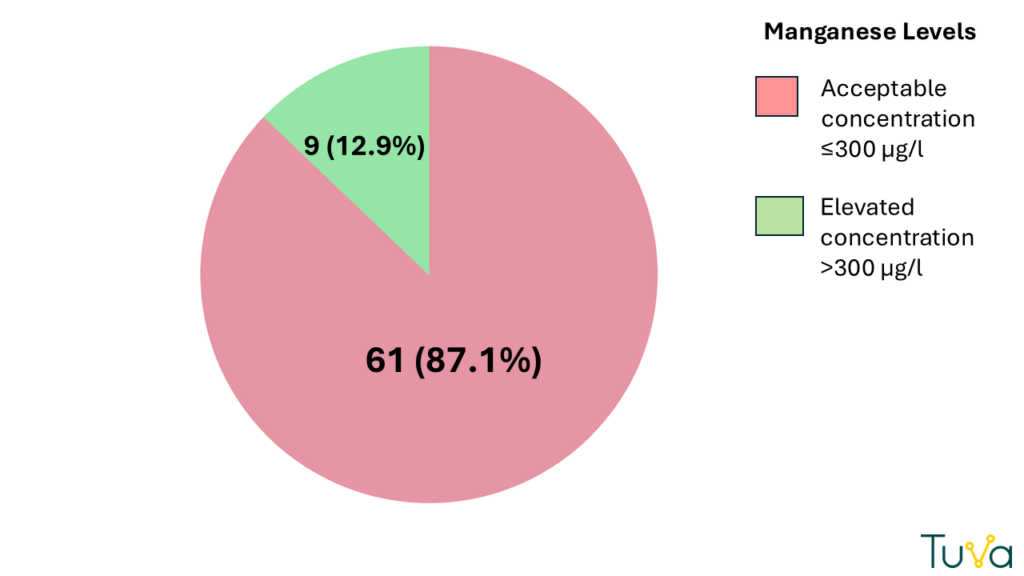

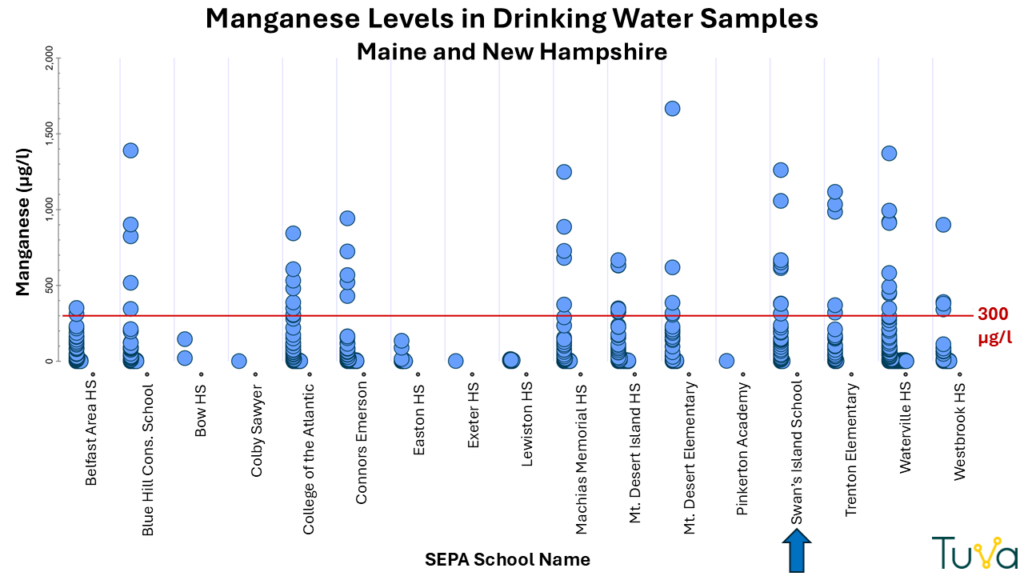

Michelle Whitman, a teacher at Swan’s Island School in Maine, is addressing a serious water quality issue on the island as part of the NIH SEPA “Communicating Data” project. Residents have long struggled with discolored, sediment-heavy water and have relied on bottled water and/or filtration systems. However, in 2024, when Michelle and her students tested local water samples for heavy metals, they uncovered a previously unknown problem: elevated manganese. Nearly 33% of tested households had manganese levels exceeding the EPA’s 50 µg/l secondary standard (a non-mandatory standard), while 13% surpassed the 300 µg/l health advisory level (Figure 1). This trend has been seen by other schools in the program as well (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Manganese levels in drinking water samples collected by Swan’s Island students. The EPA has set the health advisory level of manganese at 300 µg/l.

Figure 2. Manganese (Mn) concentrations in selected drinking water samples (2016-2024). Swan’s Island samples have elevated Mn levels in numerous samples, a trend also observed in other regions of ME and NH.

Elevated manganese levels are especially harmful to young children, particularly infants, as exposure during early development can lead to learning and behavioral issues. The EPA advises that infants under 6 months should avoid water with manganese levels above 300 µg/l or formula made with such water.

Determined to take meaningful action, Michelle and her students are leading efforts to inform and protect their community. Students will present their findings at a town meeting to raise awareness about the manganese issue and its associated health risks. To further engage the community, students will create educational posters to be displayed at the town office and organize a fundraising campaign to purchase Zerowater® pitchers and filters for affected households (https://zerowater.co.uk/pages/contaminants-reduced/manganese). These items will be made available at the town office for easy access.

In addition, Michelle and her class will collect 60-70 additional water samples to expand the reach of the program. This ongoing testing ensures the community remains informed and safe while working toward long-term solutions.

Through Michelle’s leadership, her students have taken an active role in improving their community’s water quality. By combining education, fundraising, and public outreach, they’ve turned a local environmental issue into an opportunity for positive change and engagement. Michelle’s efforts have not only fostered scientific learning but also encouraged community collaboration, ensuring a safer future for the island’s residents.